Chirps

A chirp is a signal whose frequency changes over time. Up chirps are signals whose frequency increases over time, and down chirps are signals whose frequency decreases over time. The frequency change can be linear (if the rate of change is not mentioned, it can be assumed to be linear), exponential, or some other function.

Chirps are present in many natural and man-made systems. Animals such as birds, frogs and whales create audible chirps, and bats use chirps in the ultrasonic range for echolocation. Chirps are used in radar and sonar systems to detect and track targets. Chirps are also present in music, e.g. the “glissando”.1

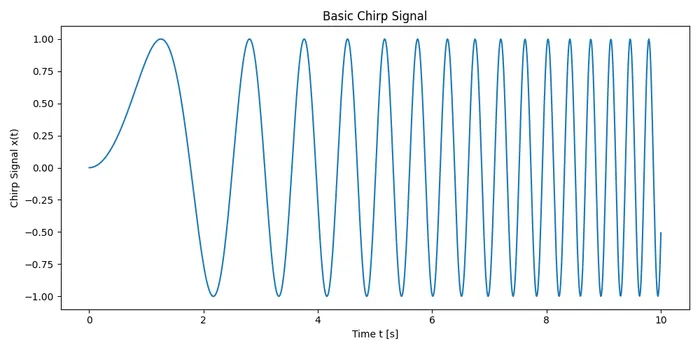

The simplest chirp signal can be created by squaring the time variable in a normal sinusoidal signal, for example:

This is a placeholder for the reference: fig-basic-chirp-signal shows a plot of this basic chirp signal . This happens to be a linear chirp, in that the frequency increases linearly over time (more on this in the Linear Chirps section).

Chirp signals are often used in radar and communication systems due to their favourable properties, such as constant amplitude, good autocorrelation properties, and resistance to Doppler shifts. The low power RF communication protocol LoRa uses chirp signals (specifically, a proprietary form of chirp spread spectrum where each symbol has a different starting frequency) to encode information.2

Basic Equations

These basic equations are applicable to most chirp signals including the linear chirps. These equations will be used in the following sections as needed.

A chirp signal can be described by the following equation:

where:

is the chirp signal at time

is the phase at time , in

Angular frequency is the rate of change of phase . Thus:

Rewriting this in terms of gives:

where:

is the initial phase at time , in (we need to add this because the definite integral only gives us the change in phase from 0 to , not the absolute phase at time )

And since , we can write:

This equation will be useful to convert from frequency to phase so that we can create the equation for the chirp signal .

Linear Chirps

A linear chirp is a chirp in which the frequency changes linearly over time. Thus:3

where:

is the frequency at time , in

is the starting frequency at time , in

is the rate of change of frequency, in

is the time, in

The phase equation for any oscillating signal is always the integral of the frequency function .

Now that we have the phase equation, we can write the equation for the linear chirp signal as (since ):

where:

is the starting phase at time , in

Exponential Chirps

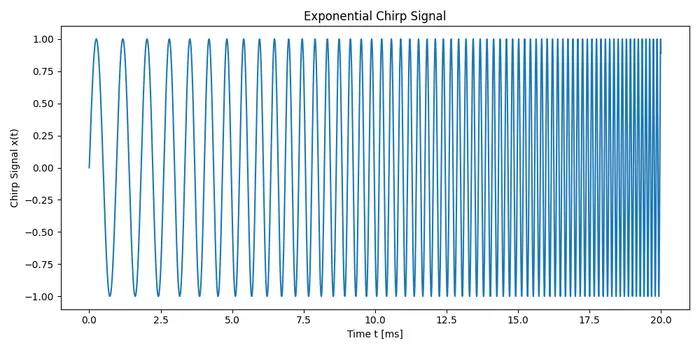

An exponential chirp (also called a geometric chirp) is a chirp in which the frequency changes exponentially over time. This means for any two points in time and where the time interval is kept constant, the frequency ratio is also kept constant.

This is a placeholder for the reference: fig-exponential-chirp-signal shows a plot of an exponential chirp signal.

The frequency of an exponential chirp is given by the following equation:3

where:

is the frequency at time , in

is the initial frequency at time , in

is the frequency ratio, a constant

is the time interval between the two points in time, in

The frequency ratio is given by the following equation:

where:

is the frequency at time , in

is the initial frequency at time , in

We can write the phase equation by integrating the frequency equation:

To get the equation for the exponential chirp signal , we substitute this equation for phase into .

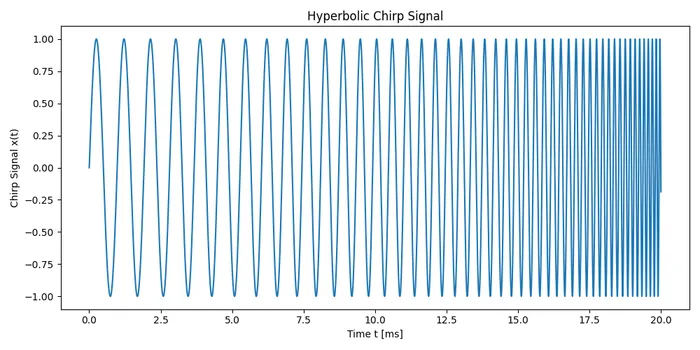

Hyperbolic Chirps

Hyperbolic chirps are used in radar and wideband active sonar systems as a way of minimizing degradation of matched filter processing when the source and target are moving with respect to each other.4 3

This is a placeholder for the reference: fig-hyperbolic-chirp-signal shows a plot of a hyperbolic chirp signal.

The frequency of a hyperbolic chirp is given by the following equation:3

where:

is the frequency at time , in

is the initial frequency at time , in

is the final frequency at time , in

is the time interval between the two points in time, in

We can integrate the frequency equation to get the phase equation :3

where:

is the phase at time , in

is the initial phase at time , in

To get the equation for the hyperbolic chirp signal , we substitute this equation for phase into .

Doppler Tolerance and Matched Filter Performance

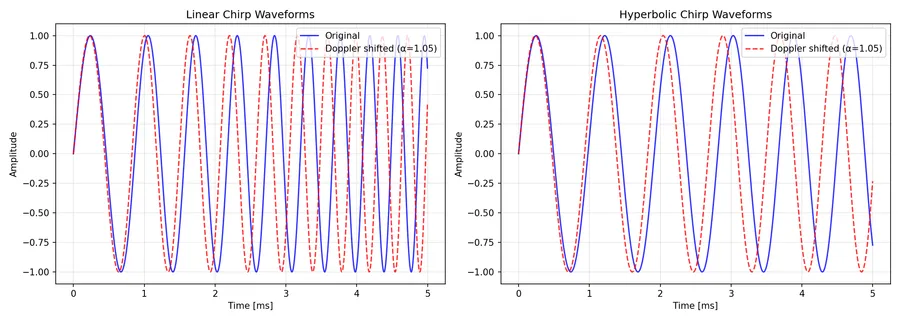

One of the most important properties of hyperbolic chirps is their Doppler tolerance. In radar and sonar systems, when a signal reflects off a moving target, the received signal undergoes a Doppler shift. This shift not only changes the frequency content but also compresses or stretches the signal in time.

Mathematically, if the transmitted signal is , the received signal from a moving target is:

where:

is the time-scaling factor due to Doppler effect

For a two-way propagation system (a.k.a. pulse-echo — like active sonar or radar), the time-scaling factor is given by the following equation:

where:

is the time-scaling factor due to Doppler effect

is the relative velocity between source and target, in

is the speed of wave propagation (speed of light for radar, speed of sound for sonar), in

The factor of 2 in the above equation comes from the fact it is a round-trip (the signal gets distorted on the way out and back).

This is a placeholder for the reference: fig-doppler-waveform-comparison shows a side-by-side comparison of the original and Doppler-shifted waveforms. This zooms into the first 5 milliseconds to show the difference more clearly.

A matched filter is a signal processing technique where the received signal is correlated with a copy of the transmitted signal to detect the presence and timing of echoes. The output produces a sharp peak when the signals align, indicating a detection.

The key problem is that when the received signal is doppler shifted, it gets scaled with respect to time. For linear chirps, this means that the received signal will only match the original signal at a single instant, as the received signal is sweeping through frequencies at a faster/slower rate. This means the correlation peak will be:

- Reduced in peak amplitude (harder to detect)

- Spread out in time (reduced range resolution)

Hyperbolic chirps have a special property: when time-scaled, they are equivalent to a time-shifted version of the original signal. This means the Doppler-shifted signal still correlates well with the original (just with a shifted started point), maintaining a sharp peak in the matched filter output.

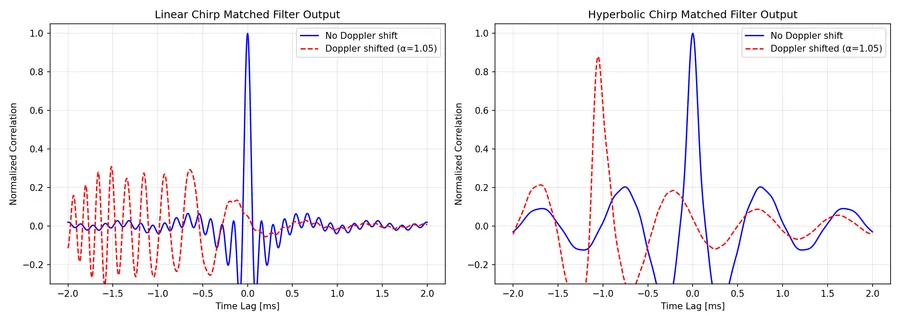

This is a placeholder for the reference: fig-doppler-matched-filter-comparison shows a side-by-side comparison of matched filter outputs for linear and hyperbolic chirps, both with and without Doppler shift (, representing approximately 5% time compression). The negative time lag for the peaks in the doppler shifted waveforms is due to the signal being compressed in time — the received signal “finishes early” and the correlation maximum shift to where the compressed signal best aligns with the original.

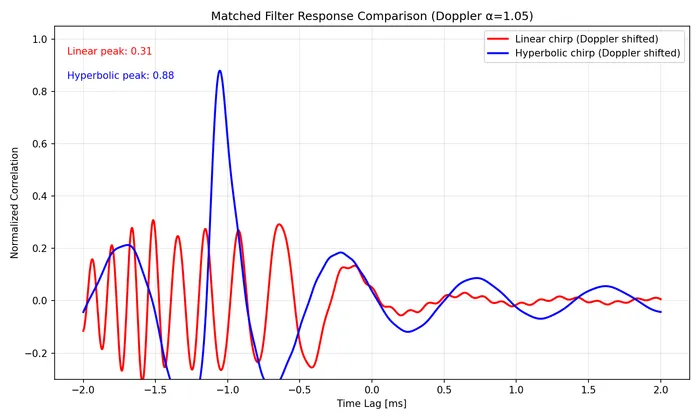

This is a placeholder for the reference: fig-doppler-tolerance-overlay provides a direct overlay comparison of just the Doppler-shifted responses, making the difference even clearer. The linear chirps correlation peak only hits a peak normalized correlation value of 0.31, whilst the hyperbolic chirp hits a peak of 0.88!

Footnotes

-

Patrick Flandrin. Time-frequency and chirps. Ecole Normale Superieure de Lyon. Retrieved 2026-01-14, from https://perso.ens-lyon.fr/patrick.flandrin/SPIE01_PF.pdf. ↩

-

Wikipedia (2025, Dec 10). LoRa [wiki]. Retrieved 2026-01-04, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LoRa. ↩

-

Wikipedia (2025, Sep 3). Chirp [wiki]. Retrieved 2026-01-12, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chirp. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Mark Readhead. Calculations of the Sound Scattering of Hyperbolic Frequency Modulated Chirped Pulses from Fluid-filled Spherical Shell Sonar Targets. Australian Department of Defence. Retrieved 2026-01-14, from https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA523424.pdf. ↩