Digital Filters

Overview

Digital filters are signal filters which act on discrete, sampled data -- as opposed to analogue filters which act on continuous signals such as fluctuating voltages.

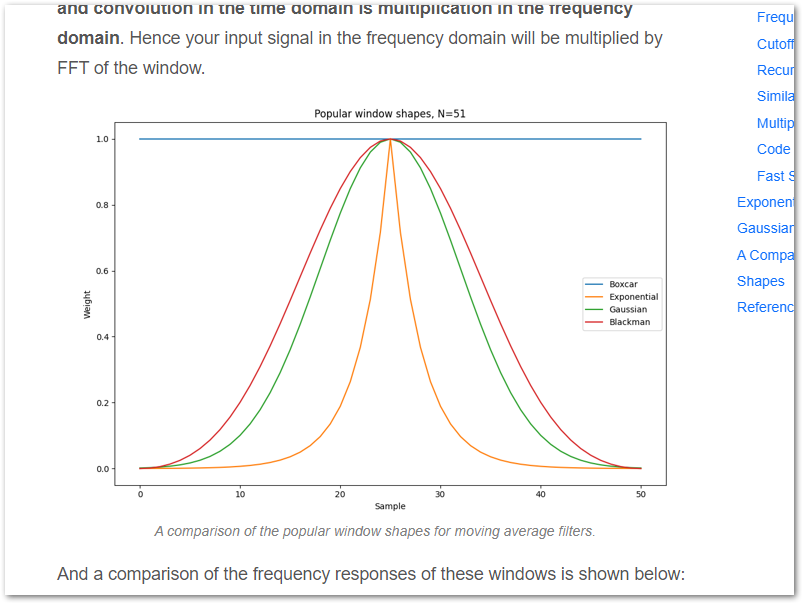

For information on the popular moving average (windowed) filters (all with a finite impulse response, FIR), including frequency responses and performance implications, see the Windowed Moving Average Filters page.

For info on the exponential moving average IIR filter (non-windowed), including the impulse response, see the Exponential Moving Average (EMA) Filter page.

Terminology

Causality

Casual filters are filters whose present output does not depend on future input. Non-casual filters are those whose present output does depend on future input. Real-time filters must be casual, but filters which are either time delayed or do not act in the time domain can be non-casual.

Cycles Per Sample

Cycles per sample is a convenient way of expressing a frequency w.r.t. the sample frequency. It is found by dividing the frequency in Hz (cycles/second) by the sampling rate in samples per second (samples/second), giving you units of cycles/sample.

Difference Equation

A difference equation is the core equation of a filter which shows how the next output value is calculated based on past and present input and output values. For example, the difference equation for an exponential moving average filter is:

Discrete Unit Sample Function

The discrete unit sample function is the digital equivalent of the analogue impulse function (the analogue impulse function is infinitely thin, but has an area of 1). The discrete unit sample function has a value of 1 at sample 1, but is 0 everywhere else. It is defined as:

\begin{align} \delta[n] = \begin{cases} 1 & n = 0 \\ 0 & n \neq 0 \\ \end{cases} \end{align} </p> This function is used for finding the impulse response of digital filters. One example is using it to find the [impulse response of the EMA filter](/programming/signal-processing/digital-filters/exponential-moving-average-ema-filter/#impulse-response). ## Converting From A Continuous Time-Domain To Normalised Discrete Time-Domain Frequency Remember, to map a continuous time-domain frequency to the discrete time-domain, use the following equation: $$ F = \frac{f}{f_s} $$ <p className="centered"> where:<br /> $ F $ is the frequency in the discrete time-domain, in $cycles/sample$<br /> $ f $ is the frequency in the continuous time-domain, in $Hz$ (or $cycles/second$)<br /> $ f_s $ is the sample frequency in the continuous time-domain, in $Hz$ (or $samples/second$)<br /></p> ## Creating Digital Filters In Python Python is a great language for experimenting with digital filters. The popular `numpy` and `scipy` libraries provide a variety of functions to make it easy to create and visualize the behaviour of a digital filter. `scipy.fftpack.fft(x)` performs a discrete Fourier transform on the input data. Passing in a window (an array of the weighting at each sample in the window) will return an array of complex numbers. `scipy.fftpack.fftshift()` shifts the result from `fft()` so that the DC component is centered in the array. `fftfreq()` converts normalized frequencies into real frequencies. `scipy.signal.freqz()` calculates the frequency response of a digital filter. It expects the coefficients of the transfer function described as: <p>\begin{align} H(z) &= \frac{Y(z)}{X(z)} \nonumber \\ &= \frac{b_0 + b_1 z^{-1} + b_2 z^{-2} + ... + b_m z^{-m}} {a_0 + a_1 z^{-1} + a_2 z^{-2} + ... + a_n z^{-n}} \\ \end{align}The order of these coefficients to freqz() is the reverse of what is standard in most places.