Assertions (assert())

assert() is a useful tool to check that certain conditions hold true during the runtime.

The basic premise behind an assert(bool_t value) is that the macro/function checks to make sure that value is true. The developer adds the checks where the expected result should be true. If the value is not true (i.e. false), the software/firmware takes specific action.

For a software application, this “specific action” may be printing out the filename and line number the assert() was raised in, and then exiting the application. For a firmware application, this may be printing out the filename and line number the assert() was raised in, and then restarting (it does not make sense to “quit” in a firmware environment).

What assert To Use?

The C standard library provides a assert() function/macro via assert.h:

#include <assert.h>

int main(void) { assert(0 == 1);}The standard behaviour for this is to evaluate the expression and it it’s false, print an error message and abort. If I run this program on Linux, I get the following message printed (and the program aborts):

main: ./main.c:4: int main(void): Assertion `0 == 1' failed.With clever use of the && operator you can add a custom message to this assert like so:

#include <assert.h>

int main(void) { assert(0 == 1 && "0 does no equal 1");}Which prints: main: ./main.c:4: int main(void): Assertion ``0 == 1 && "0 does no equal 1"' failed.. This works because the expression you actually want to test gets anded with the address of the string literal (pointer). A valid pointer can never be null, so it’s guaranteed to be true, thus the expression is just 0 == 1 && true which is logically equivalent to just 0 == 1.

The standard library assert becomes a no-op if NDEBUG is defined. For this reason the argument to assert() should have no side effects (more on this below).

You might be wondering what happens when an assert is raised on a microcontroller. “Aborting” is not really an option as it is with software running on a fully-fledged OS. Instead, the behaviour is typically overridden so that the abort message is printed out a debug serial port (and/or logged somewhere), and then the MCU is reset. Sometimes a delay is added in the assert handler before resetting to prevent fast “boot loops”. This can be beneficial to prevent user indicator LEDs from blinking unrecognizable patterns, allow time for debugging the problem, and prevent things like flash from wearing out (if you write to flash on start-up).

However, you may want to roll your own assert().

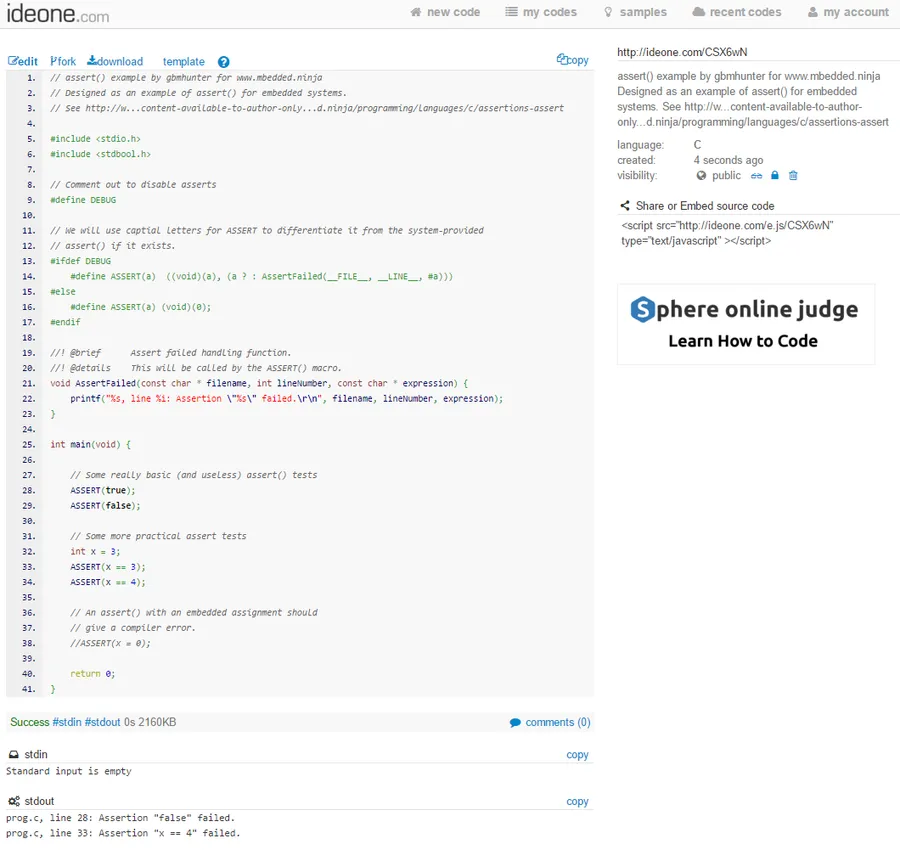

If you are looking for a full-blown assert() example, check out the compilable/testable assert() code snippet at http://ideone.com/CSX6wN.

What Should I Use assert() For?

Assertions are generally meant for checking fatal, “cannot continue” errors. For example, it’s usually a good idea to use assert to make sure a pointer is not null. If it was null, it means there is a bug in the firmware and it needs fixing. It also generally means you are not able to continue with execution. It’s not a good idea to use assert to check that a temperature sensor reading says that the current room temperature is above 20C.

Asserts usually should be used for:

- Checking pointers are non-null after allocating memory

- Function arguments are within bounds in your own application code (including making sure passed in pointers are non-null)

Assert usually should NOT be used for:

- Checking the bounds of function arguments in libraries that will be used by many people (it’s better to return an error code in this case).

- Validating user input

- Verifying something that is likely to fail (e.g. asserting that a CRC on a received packet is correct, it’s better to implement a retry mechanism).

Asserts can be great for making sure your code doesn’t reach places you expect to be unreachable. For example:

typedef enum { STATE_1, STATE_2} myStates_t;

void handleState(myStates_t state){ switch (state) { case STATE_1: break; case STATE_2: break; default: // We should never get here! assert(false); }}This also works well for if/if else/else statements, you can add an assert() to the last else if you know the code should always match against one of the previous if/else if branches.

Although it is suggested by many people to disable asserts in production releases of code, my personal opinion is that in an embedded context it usually makes more sense to leave them in so that you can catch errors early, be warned about them in a clear manner, and prevent the processor from executing off into the wild world of undefined behaviour. It might make sense to leave them enabled in much software too!

A Simple assert() Using A Macro

assert() is usually defined in C using a macro (rather than a function). This provides the ability of automatically keep track of things such as the filename and line number that the assert() was written on.

A basic assert macro could have the following definition:

#define ASSERT(exp) (exp ? : assertFailed(__FILE__, __LINE__))Note that the ternary operator is used here instead of an if statement.

assertFailed() is a function you have to write that will handle any raised assert()’s. You just need to declare that it exists in the same header file the ASSERT macro is in, and then define it in a .c file somewhere as:

void assertFailed(const char * filename, int lineNumber){ // Assuming printf() sends the data to somewhere like a serial debug port on // your embedded device printf("ERROR: Assert raised in file %s at line number %i.", filename, lineNumber);}You could then use it like this:

ASSERT(myPtr); // Makes sure pointer is not null.ASSERT(x == 4); // Makes sure x = 4ASSERT(msgLength <= bufferSize); // A common use case is to check array sizesA Note On FILE and LINE

__FILE__ and __LINE__ are special Standard Predefined Macros as defined by the C language specifications1. For more info, see the File Names And Line Numbers section of the Preprocessor page.

__FILE__ and __LINE__ can be removed from the macro in flash constrained embedded systems (storing the filename strings can take up a decent amount of flash).

Note that use of __FILE__ may not take up as much flash memory as you think, as most compilers with any sort of optimisation turned on will collate all string literals which are exactly the same into one (i.e. all the the __FILE__ pointers in the same file will point to the same string literal).

Are there any other useful preprocessor keywords? How about __func__? This gets replaced with a const char * that contains the name of the current function the macro is in. You could add that info in there too!

Printing The Failed assert() Condition

Even more useful than just having the filename and line number is also printing the expression which caused the failed assert() . Luckily, this is easy to do, using the preprocessor stringification symbol, #.

#define ASSERT(exp) (exp ? : assertFailed(__FILE__, __LINE__, #exp))The function which handled the failed assert() would then have the following declaration:

void assertFailed(const char * filename, int lineNumber, const char * expression){ // Assuming printf() sends the data to somewhere like a serial debug port on // your embedded device printf("ERROR: Assert expression %s failed in file %s at line number %i.", expression, filename, lineNumber);}Note that this would consume much more flash memory than __FILE__ alone would, as rarely any of the const char * expression string literals would be the same.

Preventing Side-Effects

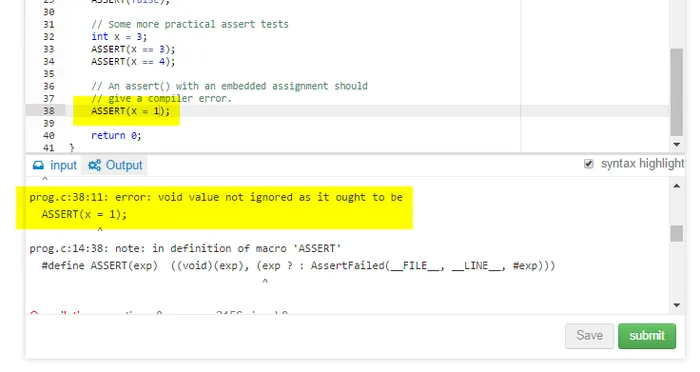

assert() checks should NOT have any side effects. That is, you should not embed assignments or function calls with side-effects inside assert() checks. This is to prevent the logic of your application changing when enabling/disabling assert()’s.

// This is goodassert(x == 3);

// This is BAD// (this makes x = 1)assert(x = 1);

// This is BAD...assuming myFunc()// has side effects. If myFunc() was a pure function, i.e.// only operated on it's inputs, contains no state, and returns a value// then this is okassert(myFunc(x));The assert() macro can be re-written to stop developers from writing assert()’s with side effects. This can be done by making clever use of the C comma operator (note that this is not the same as the comma used as a separator between variables in a function call).

#define ASSERT(a) ((void)(exp), (exp ? : assertFailed(__FILE__, __LINE__, #exp)))Is using the GCC compiler, and you write an assert with side effects, you should get the following error:

error: void value not ignored as it ought to beNote that I was using gcc-5.1 when I was presented with this error.

Complete Code Example

I have written a working assert() example at http://ideone.com/CSX6wN. It employs all of the functionality described above, including filename and line number reporting, expression printing, and syntax which disallows the use of assignments or function calls within the parameter passed to assert().

Assert With printf() Style Messages

The below macro allows you to use assert with printf() style messages:

#define LOG_ERROR(M, ...) fprintf(stderr, "[ERROR] (%s:%d) " M "\r\n", __FILE__, __LINE__, ##__VA_ARGS__)#define assertf(A, M, ...) if(!(A)) { LOG_ERROR(M, ##__VA_ARGS__); assert(A); }A working example of the above code can be found at https://ideone.com/DD1PJs.

Compile Time Asserts

You can also perform assert-like checks at compile time rather than runtime. In previous times people craftily wrote their own macros do these (or they were provided by compilers). Since C11, the standard library has provided an easy way of writing asserts that get checked at compile time. In C11, <assert.h> introduced the following macro[cppreference-c-static-assert]:

#define static_assert _Static_assertYou can use static_assert() like this:

#include <assert.h>

#define MAX_MSG_LENGTH 20#define BUFFER_SIZE 30

int main(void){ // Check we can hold the message in the buffer static_assert(MAX_MSG_LENGTH <= BUFFER_SIZE);

// You can check integer constants at compile time static_assert(4 == 4);}Because these are compile time checks, you can’t check for things that are not known until runtime.

#include <assert.h>

int main(void){ static_assert(3.14 == 3.14, "Is Pi Pi?"); // Won't work, can't check floats!

const int x = 4; static_assert(x == 4); // Can't check variables, even if they are declared const // You could in C++ with constexpr.

static_assert(myFunc()); // Can't check function return variables. You can in C++ // with constexpr.}In C23, static_assert() was turned into a keyword[cppreference-c-static-assert], so you don’t even need to #include <assert.h>!

External Links

Assert Yourself, by Niall Murphy, is a good read about using the assert() macro.

References

Footnotes

-

GeeksforGeeks. Predefined Macros in C with Examples. Retrieved 2024-03-27, from https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/predefined-macros-in-c-with-examples/. [cppreference-c-static-assert]: cppreference.com (2023, Feb 21). C - Error handling - static_assert. Retrieved 2024-03-27, from https://en.cppreference.com/w/c/error/static_assert. ↩